Causes | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment | Complications | Prevention | Takeaway | FAQs

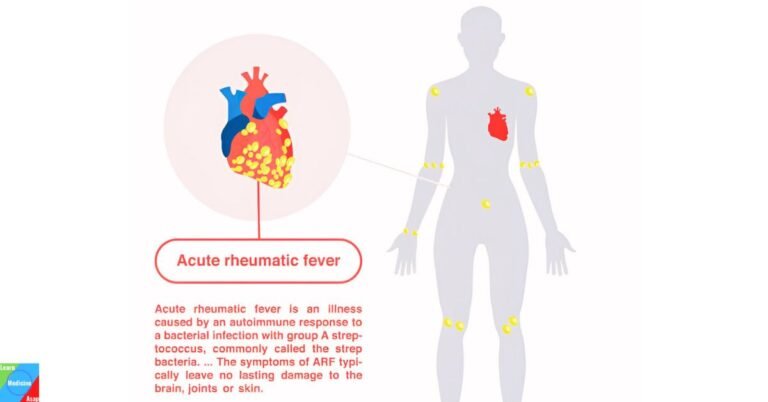

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is an inflammatory disease that can develop as a complication of untreated or inadequately treated streptococcal throat infection (strep throat). It most commonly affects children between the ages of 5 and 15, although it can occur at any age. ARF can lead to serious complications, including rheumatic heart disease, which can cause long-term damage to the heart valves.

What is acute rheumatic fever?

Acute rheumatic fever is an autoimmune inflammatory condition that follows a streptococcal throat infection. It affects multiple systems in the body, including the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease can cause permanent damage to the heart valves, leading to rheumatic heart disease, which is a major cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in young adults.

What causes acute rheumatic fever?

Acute rheumatic fever is caused by an autoimmune response to a throat infection with group A Streptococcus bacterium. The body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues, mistaking them for the bacteria. This response leads to inflammation in the heart, joints, skin, and central nervous system.

Who’s at risk for rheumatic fever?

Several risk factors are associated with an increased likelihood of developing ARF:

- Age: ARF most commonly affects children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.

- Geographic Location: The incidence of ARF is higher in certain regions, particularly in developing countries and in areas with limited access to healthcare. Endemic areas include parts of Africa, Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Latin America.

- Socioeconomic Factors: Poor socioeconomic conditions, including overcrowded living conditions, poor sanitation, and limited access to medical care, are significant risk factors.

- Genetic Predisposition: A family history of ARF or rheumatic heart disease suggests a genetic component, as certain genetic markers have been associated with an increased susceptibility.

- Previous Strep Infections: Individuals who have had repeated strep throat infections are at a higher risk. The likelihood increases with the frequency of untreated or inadequately treated streptococcal infections.

- History of ARF: Having had ARF in the past increases the risk of recurrence, particularly if further streptococcal infections occur.

- Delay in or Inadequate Treatment of Strep Throat: Delays in seeking treatment or inadequate treatment of streptococcal infections can lead to ARF. It is crucial to complete the full course of antibiotics prescribed for strep throat.

What are the symptoms of acute rheumatic fever?

The symptoms of ARF can vary widely, but here are the most common ones, described in detail:

Arthritis

One of the most common symptoms of ARF is migratory arthritis, which means the inflammation moves from one joint to another.

The joints typically affected are large ones, such as the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists. These joints become swollen, red, hot, and very painful.

Each affected joint may remain painful and swollen for a few days before the inflammation moves to another joint.

Carditis

Inflammation of the heart, known as carditis, can affect all layers of the heart, including the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium.

Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, and fatigue. In severe cases, it can lead to heart failure.

Clinically, signs such as a new heart murmur or changes in existing murmurs may be detected, indicating valve involvement, particularly the mitral and aortic valves.

Chorea (Sydenham’s Chorea)

This neurological disorder, also known as St. Vitus’ dance, is characterized by involuntary, rapid, and irregular movements.

Movements are typically more pronounced in the face, hands, and feet.

The person may also exhibit muscle weakness, emotional instability, and clumsiness.

Erythema Marginatum

This is a distinctive rash associated with ARF. The rash is typically painless and non-itchy, presenting as pink or red macules that spread outward to form a ring-like shape with clear centers.

It commonly appears on the trunk and proximal limbs but rarely on the face.

Subcutaneous Nodules

These are painless, firm lumps under the skin. They are typically found over bony prominences such as the elbows, knees, wrists, and the back of the scalp.

Nodules are usually small, about 0.5 to 2 cm in diameter, and they generally resolve without treatment within a few weeks.

Fever

A high fever often accompanies other symptoms of ARF. The fever may be sustained or intermittent, often ranging from 38.5°C (101.3°F) to 40°C (104°F).

Minor Symptoms

- Generalized Symptoms: These may include fatigue, malaise, weight loss, and a general feeling of being unwell.

- Specific Symptoms: In some cases, individuals may experience nosebleeds (epistaxis), abdominal pain, or headaches.

How is acute rheumatic fever diagnosed?

Diagnosing acute rheumatic fever (ARF) involves a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. The diagnosis is primarily based on the Jones Criteria, which include a set of major and minor criteria that help in identifying the condition. Here’s a detailed overview of how ARF is diagnosed:

Medical History

- Recent Streptococcal Infection: A history of recent sore throat or evidence of a group A streptococcal (GAS) infection within the past few weeks is crucial. This can include a positive throat culture for GAS or elevated streptococcal antibody titers.

- Previous Episodes: A history of previous episodes of ARF or rheumatic heart disease increases the likelihood of a current episode.

Physical Examination

- Joint Examination: Checking for migratory arthritis, which typically affects large joints such as the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists.

- Cardiac Examination: Listening for new heart murmurs or changes in existing murmurs, which can indicate carditis. Other signs of heart involvement include tachycardia, pericardial rubs, and signs of heart failure.

- Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue: Looking for erythema marginatum (a characteristic rash) and subcutaneous nodules.

- Neurological Examination: Assessing for chorea, which involves involuntary, rapid, irregular movements and muscle weakness.

Jones Criteria

The Jones Criteria are divided into major and minor criteria. A diagnosis of ARF requires the presence of either:

- Two major criteria, or

- One major and two minor criteria, plus evidence of a preceding streptococcal infection.

Major Criteria

- Migratory Arthritis: Inflammation of large joints that moves from one joint to another.

- Carditis: Inflammation of the heart, which may manifest as endocarditis, myocarditis, or pericarditis.

- Chorea: Neurological disorder characterized by involuntary, rapid movements.

- Erythema Marginatum: A non-itchy, pink rash with ring-like shapes.

- Subcutaneous Nodules: Small, painless lumps under the skin, usually over bony prominences.

Minor Criteria

- Fever: Temperature ≥ 38.5°C (101.3°F).

- Arthralgia: Joint pain without swelling.

- Elevated Acute Phase Reactants: Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Prolonged PR Interval: Detected on electrocardiogram (ECG), indicating delayed conduction through the atrioventricular node.

Laboratory Tests

- Throat Culture: To detect the presence of group A Streptococcus.

- Streptococcal Antibody Tests: Elevated levels of antibodies such as anti-streptolysin O (ASO) or anti-DNase B can indicate a recent streptococcal infection.

- Blood Tests: Including ESR and CRP to assess inflammation. A complete blood count (CBC) may show elevated white blood cells.

Imaging Studies

- Echocardiography: Used to detect and assess the extent of carditis. It can reveal valvular regurgitation, vegetations, or other structural abnormalities.

- Chest X-ray: May be performed to evaluate heart size and look for signs of heart failure.

Additional Tests

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): To detect prolonged PR interval and other signs of carditis.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): In cases of chorea, MRI may be used to rule out other neurological conditions.

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions that mimic ARF, such as infectious arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or juvenile idiopathic arthritis, must be ruled out through careful clinical and laboratory evaluation.

How is acute rheumatic fever treated?

Treating acute rheumatic fever (ARF) involves multiple approaches aimed at eradicating the underlying streptococcal infection, managing inflammation, relieving symptoms, and preventing recurrence. Here’s a detailed, step-by-step guide on how ARF is treated:

1. Eradication of Streptococcal Infection

Antibiotic Therapy

- Penicillin: The standard treatment involves intramuscular benzathine penicillin G. For those who cannot tolerate injections, oral penicillin V is an alternative.

- Alternative Antibiotics: For patients allergic to penicillin, erythromycin or a first-generation cephalosporin such as cephalexin may be used.

- Treatment Duration: Typically, a 10-day course of oral antibiotics is recommended to ensure complete eradication of the bacteria.

2. Anti-inflammatory Treatment

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

- Aspirin: High-dose aspirin is commonly used to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, particularly in cases of arthritis.

- Alternative NSAIDs: If aspirin is contraindicated, other NSAIDs like naproxen or ibuprofen can be used.

- Dosage: The dosage and duration of NSAID therapy depend on the severity of the symptoms and the patient’s response to treatment.

Corticosteroids

- Indications: Corticosteroids like prednisone are used in cases of severe carditis or when NSAIDs are insufficient.

- Dosage and Duration: The initial high dose is gradually tapered over several weeks as symptoms improve.

3. Management of Carditis

- Heart Failure Treatment: If carditis leads to heart failure, additional treatments such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or beta-blockers may be necessary.

- Monitoring: Regular follow-up with a cardiologist and periodic echocardiograms are essential to monitor heart function and progression of valvular disease.

4. Symptomatic Treatment

Chorea Management

- Supportive Care: Most cases of Sydenham’s chorea are self-limiting and improve with supportive care.

- Medications: In severe cases, medications such as valproic acid, carbamazepine, or corticosteroids may be prescribed to control the involuntary movements.

5 Long-term Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Benzathine Penicillin G: Intramuscular injections every 3-4 weeks are the standard prophylactic treatment.

- Oral Penicillin: An alternative for those who cannot tolerate injections, although less effective than intramuscular penicillin.

- Duration: The duration of prophylaxis depends on several factors, including age, presence of carditis, and the risk of exposure to streptococcal infections. It can range from 5 years to lifelong prophylaxis in cases with significant cardiac involvement.

6. Surgical Intervention

- Valve Surgery: In cases of severe valvular damage resulting from carditis, surgical interventions such as valve repair or replacement may be necessary.

7. Lifestyle and Supportive Measures

- Rest: Bed rest is often recommended during the acute phase to reduce cardiac workload and alleviate symptoms.

- Activity Restrictions: Physical activity may be limited until inflammation subsides and cardiac function stabilizes.

8. Education and Follow-up

- Patient and Family Education: Educating patients and their families about the importance of adherence to antibiotic prophylaxis and recognizing symptoms of streptococcal infections is crucial.

- Regular Follow-up: Regular medical follow-up ensures monitoring for potential complications, adherence to prophylaxis, and early intervention if symptoms recur.

What are the complications of acute rheumatic fever?

Acute rheumatic fever can lead to several complications, some of which can be severe and long-lasting, including:

- Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD): Chronic heart valve damage that can lead to heart failure and other cardiac complications

- Heart Failure: Due to severe carditis

- Chronic Arthritis: Joint inflammation that can persist or recur

- Neurological Complications: Persistent or recurrent episodes of Sydenham’s chorea

How is acute rheumatic fever prevented?

Preventing acute rheumatic fever primarily involves preventing streptococcal throat infections and promptly treating them when they occur:

- Prompt Treatment: Early and adequate treatment of streptococcal throat infections with antibiotics

- Prophylactic Antibiotics: Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis for individuals with a history of acute rheumatic fever to prevent recurrence

- Education and Awareness: Public health education about the importance of treating sore throats, especially in children

Takeaway

Acute rheumatic fever is a serious condition that arises from untreated streptococcal throat infections. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to manage symptoms and prevent complications. Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis can help prevent recurrences and subsequent heart damage. Public awareness and prompt treatment of strep throat are key to preventing this potentially life-threatening disease.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Can adults get acute rheumatic fever?

A1: Yes, while it is most common in children, adults can also develop acute rheumatic fever.

Q2: How long does it take to recover from acute rheumatic fever?

A2: Recovery can vary; most symptoms resolve within weeks, but some, like carditis or Sydenham’s chorea, may take longer and require prolonged treatment.

Q3: Is acute rheumatic fever contagious?

A3: Acute rheumatic fever itself is not contagious, but the streptococcal infection that triggers it is contagious.

Q4: What are the long-term effects of acute rheumatic fever?

A4: The main long-term effect is rheumatic heart disease, which can cause permanent heart valve damage and complications like heart failure.

Q5: Can acute rheumatic fever be cured?

A5: There is no cure for acute rheumatic fever, but it can be managed effectively with medication and preventive measures to reduce the risk of recurrence and complications.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/rheumatic-fever#tab=tab_1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Rheumatic Fever: All You Need to Know. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-public/rheumatic-fever.html.

- American Heart Association (AHA). (2021). Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/rheumatic-fever.

- Mayo Clinic. (2022). Rheumatic Fever. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/rheumatic-fever/symptoms-causes/syc-20354588.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (2023). What Is Rheumatic Heart Disease?. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/rheumatic-heart-disease.